President McKinley’s Coffin

From Cheat Mountain, West Virginia to McDowell, Virginia

On September 6th, 1901, during the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, socialist radical Leon Czolgosz shot President William McKinley with an Iver-Johnson .32 revolver. The crowd screamed: “Lynch him!” McKinley died September 14th. Czolgosz was convicted and electrocuted at Auburn Prison on October 29th. Prison Warden J. Warren Mead was determined Czolgosz would not become a martyr. Acid was poured into the killer’s coffin, dissolving the body.

Charlie Poole, Bascom Lunsford and other legends of country music memorialized the president’s assassination in the popular song, “McKinley’s Blues.”

McKinley he hollered, McKinley he squalled

The doctor said “McKinley, I can not find that ball”

From Buffalo to Washington…

In 1900, the year McKinley was elected to a second term and the year before his death, an elderly Confederate Veteran of the War for Southern Independence finished laboring at a job assigned by Eli Crouch, owner of a Tygart Valley farm near Elkwater, West Virginia. The old soldier, whose name and fate are lost in time, hand-carved not one, but two watering troughs from solid slabs of Cheat Mountain rock.

When curious onlookers asked what the Veteran was doing, he is said to have replied, “I’m makin’ McKinley a coffin.”

Perhaps he was expressing annoyance at what seemed to him a foolish question. Maybe it was a soldier’s foreboding of the assassination soon to take place. Or could it have been an expression of disdain for the man from Ohio who fought with the Yankees at Cedar Creek, Opequon, Fishers’ Hill and Antietam?

One of “McKinley’s Coffins,” like the old soldier, has disappeared, its fate unknown. The other remained at the Crouch home place for another 72 years. It not only provided cool spring water for Crouch’s horses, but was used to keep his catches of mountain trout fresh before being cleaned.

The Crouches were early settlers of the Tygart. Eli Crouch, who died at the age of 100 years and 6 months, was Bruce Vance’s grandfather. According to the family, records in Elkins indicate the first white child born in West Virginia was a Crouch. Upon Eli’s death in 1942, the Elkwater farm went to Vance’s uncles and Aunt Delilah. She, in turn, willed the “coffin” to Bruce.

In 1972, Bruce, his son Robin, Bruce’s brother Lohr, along with Henry H. “June” Hull and his son Dennis, journeyed from their Bull Pasture Valley home crossing the mountains to the Tygart Valley, Hull in his 1967 Jeep pickup truck and Lohr Vance in a second truck.

Hull says

although he and Bruce were “stout” men in those days and each could

easily lift 200 pounds, they had all they could handle getting the two carved

slabs loaded. After Vance returned home with his inheritance, he hired

contractor Houston Smith of Monterey to dig a trench with his backhoe, running

a water line from a spring above the Vance home.

Hull says

although he and Bruce were “stout” men in those days and each could

easily lift 200 pounds, they had all they could handle getting the two carved

slabs loaded. After Vance returned home with his inheritance, he hired

contractor Houston Smith of Monterey to dig a trench with his backhoe, running

a water line from a spring above the Vance home.

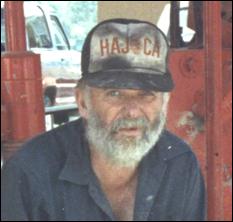

With that part of the job finished, local jack-of-all-trades and plumber David “Hink” Hiner (right) was called in to apply the finishing touches, putting the family heirloom back into service. “Hink” went about the plumbing assignment with his usual resourcefulness, and to this day the clear water flows into the hollowed rocks without a complaint.

The finely-cut stone box measures seventy-five inches long, eighteen

inches wide and fourteen inches high. The inside is nine inches deep, its floor

sloping upward from the center to a lesser depth at each end. On the top edge

of one side an overflow is cut, and at the bottom of the inside of the trough

there is a wooden plug sealing a drain hole.

The finely-cut stone box measures seventy-five inches long, eighteen

inches wide and fourteen inches high. The inside is nine inches deep, its floor

sloping upward from the center to a lesser depth at each end. On the top edge

of one side an overflow is cut, and at the bottom of the inside of the trough

there is a wooden plug sealing a drain hole.

The trough rests atop another hand-chiseled slab, about twenty-eight inches square by twelve inches thick. Into this supporting base, a small basin catches the overflow which runs out through an iron pipe, neatly leaded into a hole in the bottom just as the Confederate soldier made it 105 years ago.

The sculpting is the work of a master, as fine as a sarcophagus of

ancient Egypt. It is reported to have taken a full day’s labor to cut

each inch from the inside depth of the box. Bruce recalls being told the stone

was found near the head of a creek in a mountain hollow on the Huttonsville

side of Cheat.

The sculpting is the work of a master, as fine as a sarcophagus of

ancient Egypt. It is reported to have taken a full day’s labor to cut

each inch from the inside depth of the box. Bruce recalls being told the stone

was found near the head of a creek in a mountain hollow on the Huttonsville

side of Cheat.

Adorned with a collection of geological oddities found on the Vance farm below McDowell, Bruce and his wife Nancy have cared for “McKinley’s Coffin” since 1972. They express little doubt their sons will continue to do so “after we’re gone.”

One would hope the soul of that unknown Veteran is at peace, remembered and honored by his descendants. But even if his troubled spirit roams the Tygart Valley, he should take some comfort knowing his handiwork has found repose in another vale across the mountains.

Beside his home south of McDowell, Bruce Vance stands next to McKinley’s Coffin.